Solar energy generation in Pennsylvania is growing, as are proposals for the construction of new solar energy generation. Solar energy can be “distributed” (small-scale), meaning it is placed on the roof of a structure, the ground, or over a parking lot near a structure and primarily feeds electricity to the structure. These types of solar systems are typically defined as “accessory uses” within local government (municipal) codes.

Other solar energy development consists of medium and large projects that are not primarily designed to feed electricity to a structure on the lot where they are located. These systems are called medium- or large-scale solar, utility-scale solar, commercial-scale solar, grid-scale solar, principal-use solar, or solar farms, among other terms. As defined here, medium- and large-scale solar systems are arrays of solar panels that comprise the primary land use, or one out of two primary uses, on a particular lot (a piece of land). Medium- and large-scale solar systems, as defined here, are also built to feed energy back into the grid—not just to a structure on the site of the solar panels.

Local governments are the primary “gatekeepers” of all forms of solar energy development in Pennsylvania. Local governments include municipalities, which are municipal corporations, and counties. As defined by the Pennsylvania Legislature, a “municipal corporation” includes a “city, borough, incorporated town, township of the first or second class or any home rule municipality other than a county.” There are 2,559 municipal corporations in Pennsylvania and 67 counties. These municipalities determine whether solar energy systems may be built, and whether such systems are only allowed as accessory uses or whether medium- and large-scale solar systems may be built. Local governments also regulate issues such as the minimum required distance between solar development and lot lines (setbacks); fences and screening around solar energy development; preservation of vegetation and agriculture beneath and around solar energy development; the preservation of access to sunlight for solar energy development; and whether and how developers must “decommission” solar energy development—removing equipment from sites and restoring sites at the end of the useful life of solar equipment.

The Commonwealth of Pennsylvania plays less of a regulatory role and more of an advisory role in solar energy development. The Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) regulates the stormwater impacts of solar farms, meaning the water that runs off sites during rain or snowmelt. The DEP also provides a Solar Energy Resource Hub with guidance for local governments, schools, developers, and other entities involved in solar energy projects in Pennsylvania. Finally, the DEP commissioned an Assessment of Solar Development on Previously Impacted Mine Lands in Pennsylvania.

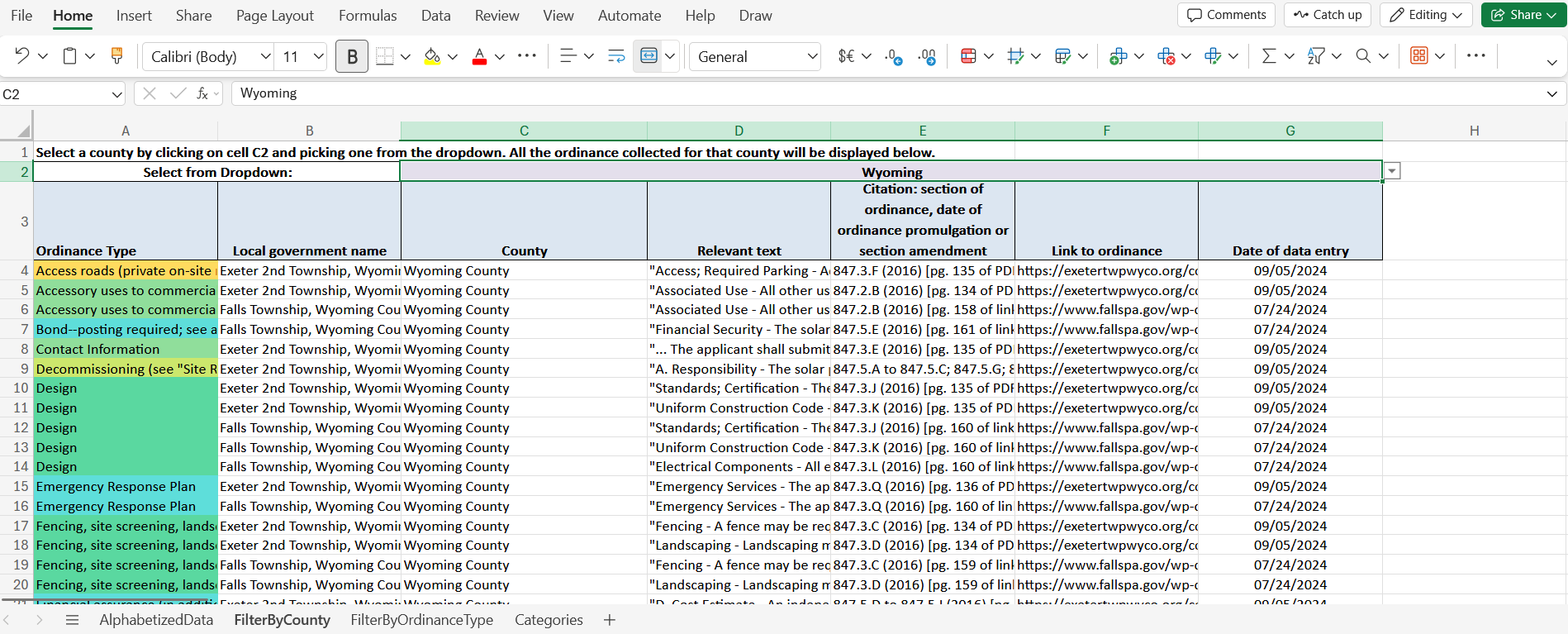

The searchable spreadsheet linked here begins to summarize local governments’ regulation of solar energy, primarily focusing on medium- and large-scale solar systems. It also contains some wind and energy storage regulations. The spreadsheet categorizes local solar energy regulations by the type of issue that they address, such as decommissioning, signs placed on sites, access to sunlight (solar easements), site screening and fencing, access roads, public road use during construction and maintenance, setbacks, regulation of the use of agricultural land, and protection of wetlands and forests. We are working to enable users to filter information by regulatory category and by local government name.

Local regulation of medium- and large-scale solar differs substantially among municipalities, as the spreadsheet shows. For example, many local governments require that solar companies construct access roads to solar sites, with ordinances setting mandatory minimum widths for such roads at 12, 14, 16, 20, and 25 feet in different municipalities and counties. Many local governments also require solar energy developers to post bonds or other financial securities to cover the cost of decommissioning the project at the end of its useful life. Local governments require solar energy developers to post financial security at 25, 100, 110, or 150 percent of decommissioning costs (minus salvage and resale value, in some cases), depending on the jurisdiction. Others require a specific amount of financial security, such as $50,000. The spreadsheet shows this and other variation, including, for example, variation among required setbacks of solar farms from the edges of lots or other land uses; the minimum required height of fences or landscaping to screen solar farms from view; the amount of prime agricultural soils that the solar farm may cover; what counts as “impervious cover” at a solar farm (the area of a lot that water cannot infiltrate); and other differences.

This work was and continues to be conducted by a team of law students and undergraduate research assistants, formerly supervised by Professor Mohamed Badissy, Penn State Dickinson Law, and now by Hannah Wiseman, Penn State Law—University Park. Many thanks to Candace Boyle, Finn Burns, Jhonathan Jesus Mariano Ordinola Diaz, Jiahang Ding, Owen Dombert, Alejandra Edwards, Binderiya Enkhamgalan, Amerika Jayme, Ariel Gootkin, Ons Jerbi, Swaraj Lakshmi Krishnakumar, Yongzheng Li, Mariem Ouslati, Patrick Quinnan, Leonard Sandler, and Benjamin Wyrosdick for excellent research work.

The DEP, the Center for Energy Law and Policy, and the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation through a grant entitled “Just Energy Transitions and Place” financially supported this work. The work is ongoing, and the linked spreadsheet is not comprehensive. Rather, the spreadsheet provides examples of the types of solar regulations that the team has located to-date in municipal ordinances in Pennsylvania. We are continuing to update, sort, and add to the spreadsheet, and we welcome suggestions for corrections and additions. Please direct any suggestions to hqw5351@psu.edu.